I’m posting this again, mainly to test out the special video post feature on WordPress, which I’ve never used before! It’s a very well-made video describing the workshop on Stoic philosophy and psychotherapy that took place at Exeter University earlier this year. I was there along with some of my friends and other academics and psychologists and therapists. The whole thing was organised by Prof. Christopher Gill. It led to the Stoic Week project, which was a huge success in terms of publicity for Stoicism, featuring in The Independent and Guardian (twice) newspapers!

Tag: Stoic

Whoever it was …

Whoever it was who said, “Fortune, I have made a pre-emptive strike against you, and I have deprived you of every single loophole,” was not basing his confidence on bolts, locks and fortifications, but on principles and arguments which are available to anyone who wants them. […] For if the mind is self-indulgent, and takes the easiest courses all the time, and retreats from unwelcome matters to what maximizes its pleasure, the consequence is weakness and feebleness born of lack of exertion; but a mind which trains and strains itself to use rationality to conceive an image of illness and pain and exile will find that there is plenty of unreality, superficiality and unsoundness in the apparent problems and horrors each of them has to offer, as detailed rational argument demonstrates. (Plutarch, On Contentment, 467C)

Plutarch was a Platonist but perhaps influenced to some extent by aspects of Stoicism.

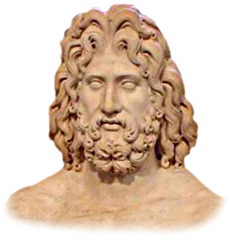

The Stoic Teachings of Zeus

Copyright © Donald Robertson, 2012. All rights reserved.

Copyright © Donald Robertson, 2012. All rights reserved.

It is wise, not listening to me but to the Logos, to agree that all things are one.

The one and only wise thing wishes and does not wish to be called by the name of Zeus. – Heraclitus, On Nature

Heraclitus’ cryptic Greek, in the passage above, can be read as implying that it is as though the voice of Nature, or Zeus, were calling us saying “all things are one”, and that wisdom consists in echoing this, in our own thoughts and words. Is he attributing these words to the divine Logos, to the voice of Zeus? The Stoics, who followed Heraclitus in many regards, also appear to attribute certain doctrines or phrases to Zeus, to God, or to Nature – all broadly equivalent terms in their pantheistic worldview.

For example, Musonius Rufus taught his students that Zeus “orders and encourages” us to study philosophy.

Stated briefly, the law of Zeus orders the human being to be good, and being good is the same thing as being a philosopher. (Lectures, 16)

He says this “commandment and law” of Nature is that humans should be “just, righteous, kind, self-controlled, magnanimous, above pain and pleasure, and devoid of all envy and treachery.” However, his most famous student, Epictetus, is our source for many more references to Stoic laws or directions attributed directly to Zeus:

For the Zeus at Olympia does not show a proud look, does he? No, but his gaze is steady, as befits one who is about to say: “No word of mine can be revoked or proved untrue.” (Discourses, 2.9.26)

However, the following passage is perhaps the most striking example of a Stoic-sounding maxim being put into the mouth of Zeus:

This is the law which God has ordained, and He says, “If you wish any good thing, get it from yourself.” (Discourses, 1.29.4)

It appears to express perhaps the most fundamental doctrine of Stoicism: that “the only good is moral good”, or that the essence of the good is virtue. Being a good person and having a good life are synonymous for the Stoics, in contrast to the other philosophical schools of their period.

So Zeus says: ei ti agathon theleis, para seautou labe or “If you wish any good thing, get it from yourself.” That obviously resonates with what Shaftesbury called the “Sovereign” precept of Epictetus’ Stoicism: “Some things are under our control and some things are not.” From this a twofold doctrine emerges: (1) the good resides squarely within our sphere of volition, in moral excellence or virtue (2) external events, beyond our control, are indifferent with regard to our happiness and wellbeing (eudaimonia). As we shall see, this twofold doctrine is repeatedly attributed to Zeus himself by Epictetus, alongside the claim that it is something that anyone may discern through considering the basic “common sense” facts of human nature.

For example, Epictetus elsewhere uses the rhetorical strategy known as apostrophe (“turning away”) when he breaks off from his dialogue with students into an imaginary conversation with Zeus himself in order to put the following words in the god’s mouth:

But what says Zeus? “Epictetus, if it were possible, I would have made both your little body and your little property free and not exposed to hindrance. But now be not ignorant of this: this body is not yours, but it is clay finely tempered. And since I was not able to do for you what I have mentioned, I have given you a small portion of us, this faculty of pursuing an object and avoiding it, and the faculty of desire and aversion, and, in a word, the faculty of using the appearances of things; and if you will take care of this faculty and consider it your only possession, you will never be hindered, never meet with impediments; you will not lament, you will not blame, you will not flatter any person.” (Discourses, 1.1)

The “law” of Zeus is elsewhere defined as (1) to guard what is our own, our reason and faculty of choice, and make good use of it; and (2) to not claim as ours what is external, or yearn for what fate has denied us, but to be willing to give up what fate has temporarily “loaned” us, as Epictetus likes to put it.

And what is the law of God? To guard what is his own, not to lay claim to what is not his own, but to make use of what is given him, and not to yearn for what has not been given; when something is taken away, to give it up readily and without delay, being grateful for the time in which he had the use of it – all this if you do not wish to be crying for your nurse and your mammy! (Discourses, 2.16.27-28)

Elsewhere, Epictetus talks about how, when death or misfortune strike, he wishes to be found obeying the commandments of Zeus. This are likewise described as (1) to use the powers, perceptions, and preconceptions, granted to him, wisely and (2) to be contented with whatever fate Zeus sends him:

For I wish to be surprised by disease or death when I am looking after nothing else than my own will, that I may be free from perturbation, that I may be free from hindrance, free from compulsion, and in a state of liberty. I wish to be found practising these things that I may be able to say to God, Have I in any respect transgressed thy commands? have I in any respect wrongly used the powers which thou gavest me? have I misused my perceptions or my preconceptions have I ever blamed thee? have I ever found fault with thy administration? I have been sick, because it was thy will, and so have others, but I was content to be sick. I have been poor because it was thy will, but I was content also. I have not filled a magisterial office, because it was not thy pleasure that I should: I have never desired it Hast thou ever seen me for this reason discontented? have I not always approached thee with a cheerful countenance, ready to do thy commands and to obey thy signals? Is it now thy will that I should depart from the assemblage of men? I depart. I give thee all thanks that thou hast allowed me to join in this thy assemblage of men and to see thy works, and to comprehend this thy administration. (Discourses, 3.5)

Again, Epictetus insists that Zeus himself has given them guidance. Perhaps recalling Heraclitus (“Listening not to me but to the Logos…”) he therefore insists the students present should listen to the guidance of Zeus and not to their mortal teacher. Again, the word of Zeus, embodied in human nature, clearly encapsulates the basic Stoic doctrine (“Follow Nature”), which divides into the twofold injunction: (1) Protect that which is your own, your reason, volition, and virtue; (2) do not grasp after that which is external, and belongs to another, or to God.

Has not Zeus given you directions? Has he not given you that which is your own, unhindered and unrestrained, while that which is not your own is subject to hindrance and restraint. What directions, then, did you bring with you when you came from him into this world, what kind of an order? Guard by every means that which is your own, but do not grasp at that which is another’s. Your trustworthiness is your own, your self-respect is your own; who then, can take these things from you? Who but yourself will prevent you from using them? But you, how do you act? When you seek earnestly that which is not your own, you lose that which is your own. Since you have such promptings and directions from Zeus, what kind do you still want from me? Am I greater than he, or more trustworthy? But if you keep these commands of his, do you need any others besides? But has he not given you these directions? (Discourses, 1.25.3-6)

Likewise, a fragment attributed as being “by [Musonius] Rufus from Epictetus” by Stobaeus reads as follows:

Of the things that exist, Zeus has put some in our control and some not in our control. In our control is the most beautiful and important thing, the thing because of which even the god himself is happy – namely, the proper use of our impressions. Such use brings freedom, prosperity, serenity, and stability; it also brings justice, law, self-control, and complete virtue. All other things he did not put in our control. Therefore, we must agree with [Zeus] the god: after we have divided matters in this way, we must concern ourselves absolutely with the things that are under our control and entrust the things not in our control to the universe. And whether it be our children, our fatherland, our body, or anything else that the universe demands, we must yield them readily.

However, although these passages suggest that the Stoics mainly attributed their central Ethical precept to Zeus, Epictetus also bemoans the fact that even Zeus has been unable to teach mankind about the nature of good and evil:

[To teach people not to pity you unnecessarily] is ineffectual and tedious – to attempt the very thing which Zeus himself has been unable to accomplish, that is, to convince all men of what things are good, and what evil. Why, that has not been vouchsafed to you, has it? Nay, this only has been vouchsafed – to convince yourself. (Discourses, 4.6.5)

Moreover, there are a couple of other cryptic passages in which Epictetus appears to attribute certain doctrines or sayings to Zeus. First, “let the better always prevail over the worse”, which seems to be taken by the Stoics to mean that the Divine Spark in man, his volition (prohairesis), is inherently able to overcome external impressions, through the faculty of judgement.

[…] nothing else can overcome volition, but it overcomes itself. For this reason too the law of God is most good and most just: “Let the better always prevail over the worse.” […] For this is a law of nature and of God: “Let the better always prevail over the worse.” Prevail in what? In that in which it is better. (Discourses, 1.29.13)

The second passage suggests that a Divine Law says that he who falsely claims to be a Stoic, or who, in general, claims things outside of his control as his own, is doomed to suffer and injure himself as a result:

For what does this [divine] law say? Let him who pretends to things which do not belong to him be a boaster, a vain-glorious man: let him who disobeys the divine administration be base, and a slave; let him suffer grief, let him be envious, let him pity; and in a word let him be unhappy and lament. (Discourses, 3.24)

There’s also a peculiar passage in Book Nine of the Stoic Lucan’s epic poem Pharsalia, about the Great Roman Civil War. The Stoic hero Cato marches his beleaguered troops through the deserts of Africa, where they endure many hardships, and suffer many casualties. However, they are inspired to persevere in the face of great adversity by Cato’s example. At one point, Cato’s army come across the only temple to Jupiter (or Zeus), under the name of Ammon, in the surrounding lands. A general who had defected from Caesar’s army, Labienus, urges Cato to consult the oracle about their fate in the civil war. However, Cato refuses to do so, because of his Stoic principles, and instead becomes a kind of oracle himself, delivering a short speech on Stoic doctrine to reproach and inspire his men.

He, filled with the god he carried in his silent mind,

poured forth from his breast words worthy of the shrine:

’What question, Labienus, do you bid me ask? Whether I prefer

to meet my death in battle, free, to witnessing a tyranny?

Whether it makes no difference if our lives be long or short?

Whether violence can harm no good man and Fortune wastes her threats

when virtue lines up against her, and whether it is enough to wish for

things commendable and whether what is upright never grows by its success?

We know the answer: Ammon will not plant it deeper in me.

We are all connected with the gods above, and even if the shrine is silent

we do nothing without God’s will; no need has deity of any

utterances: the Creator told us at our birth once and always

whatever we can know. Did he select the barren sands

to prophesy to a few and in this dust submerge the truth

and is there any house of God except the earth and sea and air

and sky and excellence? Why do we seek gods any further?

Whatever you see, whatever you experience, is Jupiter.

Let those unsure and always dubious of future events

require fortune-tellers: no oracles make me certain,

certain death does. Coward and brave must fall:

it is enough that Jupiter has said this.’ So declaring

he departed from the altars with the temples credit intact,

leaving Ammon to the peoples, uninvestigated.

So Cato is portrayed as saying that he does not need to consult Zeus in a temple. Zeno reputedly said that the ideal Stoic Republic, incidentally would have no place for temples. Zeus is all around us, in whatever we see or hear. Moreover, he has planted the seed of virtue, knowledge of our goal in life, within us, including the clue that death is certain for all men. It’s only what we can know from within, without depending on external sources of information, that’s of absolute moral importance – otherwise such knowledge would lie in the hands of fate rather than within our own power. Perhaps because we depend only on ourselves for knowledge of the good, we can grasp it with complete certainty, which provides wisdom with a special security or stability, once attained.

Finally, the famous Hymn to Zeus of Cleanthes. Epictetus quotes this repeatedly, although never more than the first four lines below, and sometimes the first line only. This doesn’t tell us any more about the laws or commandments attributed by Stoics to Zeus but it’s the perfect expression of their commitment to “Follow Nature” or “Follow God”, namely Zeus, in all they do:

Lead me on, O Zeus, and thou Destiny,

To that goal long ago to me assigned.

I’ll follow readily but if my will prove weak;

Wretched as I am, I must follow still.

Fate guides the willing, but drags the unwilling.– Cleanthes, Hymn to Zeus

Invictus by William Ernest Henley

Out of the night that covers me,

Black as the Pit from pole to pole,

I thank whatever gods may be

For my unconquerable soul.

In the fell clutch of circumstance

I have not winced nor cried aloud.

Under the bludgeonings of chance

My head is bloody, but unbowed.

Beyond this place of wrath and tears

Looms but the Horror of the shade,

And yet the menace of the years

Finds, and shall find, me unafraid.

It matters not how strait the gate,

How charged with punishments the scroll.

I am the master of my fate:

I am the captain of my soul.

William Ernest Henley (1849-1903)

“For what shall it profit [ôphelei] a man, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul?” (Mark, 8.36)

“No man can serve two masters: for either he will hate the one, and love the other; or else he will hold to the one, and despise the other. Ye cannot serve God and mammon.” (Matthew, 6.24)

What if we were to view life as consisting of a series of “transactions”, in which our own actions and character are “spent” in exchange for various things? According to the Stoics, virtue is always profitable, because it is a reward enough in itself but also leads to many other good things, such as friendship. Accepting that your fate entails the occasional loss of external things is the price nature demands for your sanity. If the price you pay for external things is that you enslave yourself to them or to other people, says Epictetus, then be grateful that if you renounce them by saving your freedom you have profited insofar as you put a higher value upon that.

This metaphor goes back at least as far as Socrates, who says in Plato’s Phaedo:

The exchange of one fear or pleasure or pain for another fear or pleasure or pain, which are measured like coins, the greater with the less, is not the exchange of virtue. O, my dear Simmias, is there not one true coin, for which all things ought to exchange?—and that is wisdom; and only in exchange for this, and in company with this, is anything truly bought or sold, whether courage or temperance or justice. …in the true exchange, there is a purging away of all these things, and temperance, and justice, and courage, and wisdom herself are a purgation of them.

The early Stoics reputedly defined the good as, among other things, that which is lusiteles or “profitable” (Diogenes Laertius, Lives, 7.98). According to Diogenes Laertius, this term was used as a synonym for the good specifically “because it pays back what is expended on it, so that it exceeds in benefit a mere repayment of the effort”. However, the same concept is appealed to by the late Roman Stoics. For example, Epictetus refers to the incident when a thief stole his (relatively valuable) iron lamp during the night:

That is why I lost my lamp, because in the matter of keeping awake the thief was better than I was. However, he bought a lamp for a very high price; for a lamp he became a thief, for a lamp he became untrustworthy, for a lamp he became like a wild-beast. This seemed to him to be profitable [lusiteles]. (Discourses, 1.29.21)

He also alludes here to another Stoic theory, which held that insofar as we abandon reason and hand over our actions to our passions we become like animals rather than rational human beings. By placing too much value on external objects we risk sacrificing our very humanity. At times, indeed, this analogy with financial transactions is made very explicit in Stoic writings:

[…] and bear in mind that, if you do not act the same way that others do, with a view to getting things which are not under our control. you cannot be considered worthy to receive an equal share with others. […] You will be unjust, therefore, and insatiable, if, while refusing to pay the price for which such things are bought, you want to obtain them for nothing. Well, what is the price for heads of lettuce? An obol, perhaps. If, then, somebody gives up his obol and gets his heads of lettuce, while you do not give your obol, and do not get them, do not imagine that you are worse off than the man who gets his lettuce. For as he has heads of lettuce, so you have your obol which you have not given away.

Now it is the same way also in life. You have not been invited to somebody’s dinner party? Of course not; for you didn’t give the host the price at which he sells his dinner. He sells it for praise; he sells it for personal attention. Give him the price, then, for which it is sold, if it is to your interest. But if you wish both not to give up the one and yet to get the other, you are insatiable and a simpleton. Have you, then, nothing in place of the dinner? Indeed you have; you have not had to praise the man you did not want to praise; you have not had to put up with the insolence of his doorkeepers. (Enchiridion, 25)

Likewise, we’re told that for the early Stoics the most important synonym of the good (agathos) was the noun “benefit” (ôpheleia) or “help” (yes, perhaps like the name of Hamlet’s “girlfriend”, Ophelia). This word can mean the “help” a physician provides to a patient, military support, but also help or assistance in a more general sense, including financial assistance, and it is sometimes also translated as a “profit”.

What, must you lose a bit of money so as to suffer damage, and does the loss of nothing else damage a man? Yet, if you lost your skill in the use of language or in music, you would regard the loss of it as damage but if you are going to lose self-respect and dignity and gentleness, do you think that does not matter? […] What does the adulterer lose? He loses the man of self-respect that was, the man of self-control, the gentleman, the citizen, the neighbour. What doe the man lose who is given to anger? Something else. Who is given to fear? Something else. No one is wretched without loss and damage. Furthermore, if you look for your loss in money, all those whom I have just mentioned suffer neither injury nor loss; nay, if it so chance, they even get gain and profit [ôpheleia], when, through some of their deeds just mentioned they also acquire money. […] Is there, then, no such thing as a faculty of the mind, the possession of which means gain to a man, and the loss, injury? –What faculty do you mean? Have we not a natural sense of self-respect [which is lost or harmed]? (Discourses, 2.10.14-22)

In other words, “the good” was interpreted as analogous to something profitable in a financial transaction or, as we might say, it’s a “good investment” on our part, one that “repays” everything we put into it. We might say the Stoic refuses to “sell out” and abandon his fundamental principles for material gain. There are, in fact, many references to the metaphor of financial transactions in the surviving Stoic literature and so this concept appears to have been a very old and important one in the Stoic tradition. It seems likely that the founders of Stoicism, whose writings are almost entirely lost to us now, may have written more on the subject, which inspired the later Roman Stoics to continue the theme.

Thus then in life also the chief business is this: distinguish and separate things, and say, Externals are not in my power: will is in my power. Where shall I seek the good and the bad? Within, in the things which are my own. But in what does not belong to you call nothing either good or bad, or profit [ôpheleia] or damage or any thing of the kind. (Discourses, 2.5, 4-5)

What then is being bought and sold?

Do you suppose that you can do the things you do now, and yet be a philosopher? Do you suppose that you can eat in the same fashion, drink in the same fashion, give way to anger and to irritation, just as you do now? You must keep vigils, work hard, overcome certain desires, abandon your own people, be despised by a paltry slave, be laughed to scorn by those who meet you, in everything get the worst of it, in office, in honour, in court. Look these drawbacks over carefully, and then, if you think best, approach philosophy, that is, if you are willing at the price of these things to secure absence of irrational passions [apatheia], freedom [eleutheria], and absence of distress [ataraxia]. (Discourses, 3.15.8-12; cf. Enchiridion, 29)

Essentially, we are selling our own essential nature as rational beings, our ruling faculty (hêgemonikon) or volition (prohairesis), into slavery. More specifically, Epictetus repeatedly refers to the price we are willing to pay for:

- “Absence of irrational passions” (apatheia), sometimes translated as tranquillity or calm

- “Absence of distress” (ataraxia), sometimes translated as peace of mind

- “Freedom” (eleutheria), which contrasts with the many references to “slavery” in Stoic writings

Hence, we are by nature “free” but sell ourselves, throughout life, in a way that must, to the ancient Greeks and Romans, have recalled the selling of a slave, a metaphor widespread in Stoic literature.

Now it so happens that the rational and the irrational are different for different persons, precisely as good and evil, and the profitable and the unprofitable, are different for different persons. It is for this reason especially that we need education, so as to learn how, in conformity with nature, to adapt to specific instances our preconceive idea of what is rational and what is irrational. But for determining the rational and the irrational, we employ not only our estimates of the value of external things, but also the criterion of that which is in keeping with one’s own character. […] For you are the one that knows yourself, how much you are worth in your own eyes and at what price you sell yourself. For different men sell themselves at different prices. (Discourses, 1.2.11)

Study these things, these judgements, these arguments, look at these examples, if you wish to have freedom [eleutheria], if you desire the thing itself in proportion to its value. And what wonder is there if you buy something so great at the price of things so many and so great? (Discourses, 4.1.170-172)

The price of being a philosopher, and fulfilling our potential as rational beings, can be particularly high but the rewards make it a profitable investment.

But that this may take place [the attainment of wisdom] a man must accept no small troubles, and must miss no small things. You cannot wish for a consulship and at the same time wish for this; you cannot have set your heart upon having lands and this too; you cannot at the same time be solicitous for your paltry slaves and yourself too. But if you wish for any one of the things that are not your own, what is your own is lost. This is the nature of the matter: Nothing is done except for a price [proika ouden ginetai]. And why be surprised? […] For absence of irrational passions [apatheia], then, for absence of distress [ataraxia], for sleeping when you are asleep, and being awake when you are awake, for fearing nothing, for being in great anxiety about nothing, are you unwilling to spend anything, to make any exertion? But if something that belongs to you be lost while you are engaged in these affairs, or be spent to no purpose, or someone else get what you ought to have got, are you going to be vexed immediately at what has happened? Will you not balance off what you are getting in return for what, how much in return for how much? Nay, do you wish to get such valuable things for nothing? And how can you? “One serious business [has no partnership] with another.”

You cannot be continually giving attention to both externals and your own ruling faculty [hêgemonikon]. But if you want the former, let the latter go; otherwise you will have neither the latter nor the former, being drawn in both directions. (Discourses, 4.10.18-20)

The proverb “One serious business has no partnership with another” resembles “You cannot serve God and mammon.” Also, “Do you wish to get such valuable things for nothing?”, etc., might be seen to resemble Spinoza’s “All excellent things are as difficult as they are rare.”

Your paltry oil gets spilled, your miserable wine stolen; say to yourself, “This is the price paid for absence of irrational passions [apatheia], this is the price for absence of distress [ataraxia].” Nothing is got without a price. (Enchiridion, 12)

In short, it’s possible that the phrase “nothing is got without a price”, which occurs twice in Epictetus, is being presented as a maxim employed in Stoicism, albeit one which could have been an already-established folk-saying.

Before the Stoics, in Plato’s Phaedo, Socrates uses the analogy of financial transaction to suggest that men who show courage in one situation out of fear of another, or moderation in one area for the sake of licence in another, are doing so at no profit and that the only “valid currency” which pleasures and pains should be exchanged for the sake of, is wisdom (Phaedo, 69ab). When we endure pain or forbear pleasure for wisdom, we have genuine virtue, otherwise we have pseudo-virtues. Yet if men are willing to suffer danger for lust, we might add, or to sacrifice pleasure to avoid danger, then this proves that virtue is possible, and lovers of wisdom should be even more willing than these men to do the same things for greater profit. If men are willing to show great courage and self-discipline for small change then why are we not willing to do so for the chief good in life?

Stoicism in the Poetry of Persius

Persius was a Roman poet and satirist (34-62 AD), who was apparently schooled in Stoic philosophy from adolescence and explicitly refers to it in his surviving writings. He was a contemporary of the philosopher Seneca, whom he apparently met, and was friends with Seneca’s nephew, the Stoic epic-poet Lucan, although his own mentor was Lucius Annaeus Cornutus, also a Stoic.

Persius’ fifth Satire is actually dedicated to Cornutus, focuses on Stoic philosophy, and expresses his gratitude to the man who taught him “the Stoic way of life”. Some excerpts that address relevant themes are as follows:

Has philosophy taught you to live

a good upstanding life? Can you tell the true from the specious,

alert for the false chink of copper beneath the gold?

Have you settled what to aim for and also what to avoid,

marking the former list with chalk and the other with charcoal?

Are your wants modest, your housekeeping thrifty? Are you nice to your friends?

Do you know when to shut your barns and throw them open? […]

Well then, two hooks are pulling on opposite ways.

Which will you follow, this or that? Your loyalty is bound

to vacillate, obeying and desecrating each master in turn.

Even if you once succeed in making a stand and defying

their incessant orders, you can’t say ‘I’ve broken my bonds!’

For a dog may snap its fastening after a struggle, but still

as it runs away a length of chain trails from its neck.

Stoicism in Horace’s Satires

Stoicism in Horace’s Satires

The Roman poet Horace (65- 8 BC) explicitly refers to Stoicism several times in his Satires and Epistles, and there appear to be many more Stoic influences scattered throughout his work. Horace studied philosophy in Athens but scholars disagree as to whether he was primarily a Stoic, an Epicurean, or an eclectic.

The Roman poet Horace (65- 8 BC) explicitly refers to Stoicism several times in his Satires and Epistles, and there appear to be many more Stoic influences scattered throughout his work. Horace studied philosophy in Athens but scholars disagree as to whether he was primarily a Stoic, an Epicurean, or an eclectic.

One of the Satires (2.7) describes a speech delivered to Horace during the festival of Saturnalia by his own slave, called Davus, who had learned Stoicism from a servant of the (perhaps fictional) Stoic philosopher and poet Crispinus.

Who then is free? The wise man who is master of himself,

who remains undaunted in the face of poverty, chains and death,

who stubbornly defies his passions and despises positions of power,

a man complete in himself, smooth and round, who prevents

extraneous elements clinging to his polished surface, who is such

that when Fortune attacks him she maims only herself. Can you

lay claim to a single one of these qualities? A woman demands

a small fortune, bullies you, slams the door, saturates you

with cold water – and invites you back. Tear that degrading yoke from your neck! Come on, say you are free! You can’t.

For a cruel master is riding your soul, jabbing the spurs

in your weary flanks, and hauling round your head when you shy. […]Moreover, you can’t stand so much as an hour of your own company

or spend your leisure properly; you avoid yourself like a truant

or fugitive, hoping by drink or sleep to elude Angst.

But it’s no good, for that dark companion stays on your heels.

The first excerpt above resembles several passages from the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius (121-180 AD), written over 200 years later:

Are you affected by pain or pleasure? Your senses must look to that. Did something stand in the way of your impulse? If you exercised your impulse without reservation the hindrance will be detrimental to you as a rational being, but if you anticipated the obstacle, you are not yet harmed or hindered. As to the operations of your intellect, no other person is in a position to hinder them; for neither fire, nor steel, nor a tyrant, nor abuse, can affect the mind in any way. When it has become a ‘well-rounded sphere’, it always remains so. (8.41)

He repeats this metaphor of the sphere again, attributing it to the presocratic philosopher Empedocles:

There are three things of which you are composed: body, breath, and mind. Of these, the first two are your own in so far as it is your duty to take care of them; but only the third is your own in the full sense. So if you will put away from yourself—that is to say, from your mind—all that others do or say, and all that you yourself have done or said, and all that troubles you with regard to the future, and all that belongs to the body which envelops you, and to the breath conjoined with it, or is attached to you independently of your will, and all that the vortex whirling around outside you sweeps in its wake, so that the power of your mind, thus delivered from the bonds of fate, may live a pure and unfettered life alone with itself doing what is just, desiring what comes to pass, and saying what is true—if, I say, you will put away from your ruling centre all that accretes to it from the affections of the body, and all that lies in the future or in time gone by, and make yourself, in Empedocles’ words, ‘a well-rounded sphere rejoicing in the solitude around it’, and strive to live only the life that is your own, that is to say, your present life, then you will be able to pass at least the time that is left to you until you die in calm and kindliness, and as one who is at peace with the guardian-spirit that dwells within him. (12.3)

Elsewhere, Marcus appears to refer once more to this Empedoclean “sphere”:

The soul is “a sphere truly shaped”, when it neither projects itself towards anything outside nor shrinks together inwardly, neither expands nor contracts, but irradiates a light whereby it sees the reality of all things and the reality that is in itself. (Meditations, 11.12)

Empedocles was a very ancient Pythagorean-influenced philosopher. The Stoics in general make many references to Pythagorean theories and practices, which this should probably be grouped alongside. It’s possible that Marcus had read this passage from Horace and was influenced by it. However, it may be more likely that they are both drawing upon a third, older, unnamed Stoic source, that makes use of this concept from Empedocles.

The second excerpt from Horace above, about “that dark companion”, also resembles a Pythagorean text called The Golden Verses, which is cited by both Epictetus and Seneca, and clearly played an important role in Stoicism:

Men shall you find whose sorrows themselves have created,

Wretches who see not the Good, that is too near, nothing they hear;

Few know how to help themselves in misfortune.

That is the Fate that blinds humanity; in circles,

Hither and yon they run in endless sorrows;

For they are followed by a grim companion, disunion within themselves;

Unnoticed; never rouse him, and fly from before him!

Father Zeus, O free them all from sufferings so great,

Or show unto each the daemon, who is their guide!

Cato’s Speech on Stoic Philosophy

From Lucan’s The Civil War

(Quotations from the translation by Susan H. Braund.)

The poet Lucan (39-65 AD) was the nephew and student of the Stoic philosopher Seneca the Younger (4-65 AD), and his epic The Civil War (De Bello Civili), also known as the Pharsalia after the Battle of Pharsalus, is steeped in Stoic philosophical themes and terminology. It describes the Great Roman Civil War (49-45 BC) between Julius Caesar and the forces of the Roman Senate led by Pompey.

In the Pharsalia, Cato the Younger (95-46 BC) is portrayed as a Stoic hero or warrior-sage, because of his defence of the Roman Republic and defiance of the tyrant Julius Caesar. In Book Two, Cato is introduced as follows by Brutus:

‘Of Virtue long ago expelled and banished from all lands

you are now the sole support, and Fortune will not with any whirlwind

strike her from you: I call on you, as I hesitate and waver,

to guide and reinforce me with your resolute strength.’

Then Cato’s character is described by Lucan:

This was the character and this the unswerving creed

of austere Cato: to observe moderation, to hold to the goal,

to follow nature, to devote his life to his country,

to believe that he was born not for himself but for all the world.

In his eyes to conquer hunger was a feast, to ward off winter

with a roof was a mighty palace, and to draw across

his limbs the rough toga in the manner of the Roman citizen of old

was a precious robe, and the greatest value of Venus

was offspring: for Rome he is father and for Rome he is husband,

keeper of justice and guardian of strict morality,

his goodness was for the state; into none of Cato’s acts

did self-centred pleasure creep in and take a share.

In Book Nine, Cato marches his beleaguered troops through the deserts of Africa, where they endure many hardships, and suffer many casualties. However, they are inspired to persevere in the face of great adversity by Cato’s example. At one point, Cato’s army come across the only temple to Jupiter (or Zeus), under the name of Ammon, in the surrounding lands. A general who had defected from Caesar’s army, Labienus, urges Cato to consult the oracle about their fate in the civil war. However, Cato refuses to do so, because of his Stoic principles, and instead becomes a kind of oracle himself, delivering a short speech on Stoic doctrine to reproach and inspire his men.

He, filled with the god he carried in his silent mind,

poured forth from his breast words worthy of the shrine:

’What question, Labienus, do you bid me ask? Whether I prefer

to meet my death in battle, free, to witnessing a tyranny?

Whether it makes no difference if our lives be long or short?

Whether violence can harm no good man and Fortune wastes her threats

when virtue lines up against her, and whether it is enough to wish for

things commendable and whether what is upright never grows by its success?

We know the answer: Ammon will not plant it deeper in me.

We are all connected with the gods above, and even if the shrine is silent

we do nothing without God’s will; no need has deity of any

utterances: the Creator told us at our birth once and always

whatever we can know. Did he select the barren sands

to prophesy to a few and in this dust submerge the truth

and is there any house of God except the earth and sea and air

and sky and excellence? Why do we seek gods any further?

Whatever you see, whatever you experience, is Jupiter.

Let those unsure and always dubious of future events

require fortune-tellers: no oracles make me certain,

certain death does. Coward and brave must fall:

it is enough that Jupiter has said this.’ So declaring

he departed from the altars with the temples credit intact,

leaving Ammon to the peoples, uninvestigated.

This is a brief excerpt from my book, The Philosophy of Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy: Stoic Philosophy as Rational and Cognitive Psychotherapy, which is now in its revised second edition, from Routledge.

Update: Since I wrote this article, people have been asking me for a short guide so I created a five-page PDF called The Stoic Therapy Toolkit, which you can download free of charge from my e-learning site.

Copyright © Donald Robertson, 2010. All rights reserved.

It is difficult, probably impossible, to do justice to the variety of therapeutic concepts, strategies, and techniques recommended by Stoic philosophers in an outline such as this. Nevertheless, I hope that by attempting to do so in relatively plain English, I will help to clarify their “art of living” somewhat, in a manner that may be of service to those who wish to make use of classical philosophy in modern life, for the purposes of self-help or personal development. It probably requires the self-discipline for which Stoics were renowned to follow a regime like this in full, and I imagine that the intention was to begin by attempting one step at a time. I certainly don’t propose this as an evidence-based treatment protocol but rather as an attempt to reconstruct the Stoic regime for discussion.

General

The chief goal of Stoicism, from the time of its founder Zeno, was expressed as “follow nature”. Chrysippus distinguished between two senses implicit in this: following our own nature and following the Nature of the world. Hence, Epictetus later expressed a general principle at the start of his famous Handbook, which the latterday Stoic the Early of Shaftesbury called the “Sovereign” precept of Stoicism:

Some things are under our control, while others are not under our control. Under our control are conception [the way we define things], intention [the voluntary impulse to act], desire [to get something], aversion [the desire to avoid something], and, in a word, everything that is our own doing; not under our control are our body, our property, reputation, position [or office] in society, and, in a word, everything that is not our own doing. (Enchiridion, 1)

Those things that our under our control, essentially our own voluntary thoughts and actions, should be performed in harmony with our nature as rational beings, i.e., with wisdom and the other forms of excellence (arete). Those things outside of our direct control should be accepted as Fated by the “string of causes” that forms the universe, as if they were the Will of God, and indifferent with regard to the perfection of our own nature, which constitutes human “happiness” or flourishing (eudaimonia). Following nature in this way, according to the Stoics, is living wisely and leads to freedom (eleutheria), fearlessness (aphobia), overcoming irrational fear and desire (apatheia), absence of distress (ataraxia), serenity (euroia) and a “smooth flow of life”.

Mornings

1. Meditation

1.1. Take time to calm your mind and gather your thoughts before preparing for the day ahead. Be still and turn your attention inward, withdraw into yourself, or isolate yourself from others and walk in silence in a pleasant and serene environment.

1.2. The View from Above. Observe (or just imagine) the rising sun and the stars at daybreak, and think of the whole cosmos and your place within it.

2. The Prospective Morning Meditation

2.1. Mentally rehearse generic precepts, e.g., the “Sovereign” general precept of Stoicism: “Some things are under our control and others are not”.

2.2. Mentally rehearse any potential challenges of the day ahead, and the specific precepts required to cope wisely with them, perhaps making use of the previous evening’s self-analysis. When planning any activity, even something trivial like visiting a public bath, imagine beforehand the type of things that could go wrong or hinder your plans and tell yourself: “I want to do such-and-such and at the same time to keep my volition [prohairesis] in harmony with nature” (Enchiridion, 4). That way if your actions are later obstructed you can say: “Oh well, this was not all that I had willed but also to keep my volition in harmony with nature and I cannot do so if I am upset at what’s going on” (Enchiridion, 4). (In other words, plan to act with the “reserve clause” for you are not upset by things but by your judgement about what you desired to achieve or avoid, and what is good or bad.)

2.2.1. Praemeditatio Malorum. Periodically contemplate apparent “catastrophes” such as illness, poverty, bereavement and especially your own death, rehearse facing such calamities “philosophically”, i.e., with rational composure, in order to overcome your attachment to external things (Enchiridion, 21). Contemplate the uncertainty of the future and the value of enjoying the here and now. Remember you must die, i.e., that as a mortal being each moment counts and the future is uncertain.

3. Contemplation of the Sage

3.1. Periodically contemplate the ideal of the Sage, try to put his philosophical attitudes into a few plain words, what must he tell himself when faced with the same adversities you must overcome? Memorise these precepts and try to apply them yourself. Adopt a role-model such as Socrates, or someone whose wisdom and other virtues you admire. When you’re not sure how to handle some encounter, ask yourself: “What would Socrates or Zeno have done in this situation?” (Enchiridion, 33)

Throughout the Day

1. Mindfulness of the Ruling Faculty (prosoche). Identify with your essential nature as a rational being, and learn to prize wisdom and the other virtues as the chief good in life. Continually bring your attention back to your character, actions, and judgements, in the here and now, during any given situation. When dealing with externals, be like a passenger who has temporarily gone ashore on a boat trip, keep one eye on the boat at all times (on yourself, your character) and be prepared at any moment to have to return onboard at the call of the captain, i.e., to abandon externals and give your whole attention again to yourself, your own attitudes and actions (Enchiridion, 7). As if you were walking barefoot and cautious not to tread on something sharp, be mindful continually of your leading faculty (your intellect and volition) and guard against it being harmed (corrupted) by your own foolish actions (Enchiridion, 38). All of your attention should focus on the care of your mind (Enchiridion, 41). In response to every situation in life, ask yourself what faculty or virtue nature has given you to best deal with it, e.g., courage, restraint, etc., and continually seek opportunities to exercise these virtues (Enchiridion, 10).

2. Indifference & Acceptance. View external things with indifference. Tell yourself: “For me every event is beneficial if I so wish, because it is within my power to derive benefit from every experience” (Enchiridion, 18) – cf. Nietzsche: “From the military school of life [Stoicism?]: What does not kill me can only make me stronger.” Serenely accept the given moment as if you had chosen your own destiny, “will your fate” after it has happened (Enchiridion, 8). Accept the hand which fate has dealt you.

3. Evaluating Profit (lusiteles). Think of life as a series of transactions, selling your actions and judgements in return for experiences. What does it profit you to gain the whole world if you lose yourself? However, virtue is always profitable, because it is a reward enough in itself but also leads to many other good things, such as friendship. Accepting that your fate entails the occasional loss of external things is the price nature demands for your sanity (Enchiridion, 12). If the price you pay for external things is that you enslave yourself to them or to other people then be grateful that if you renounce them you have profited by saving your freedom, if upon that you put a higher value (Enchiridion, 25).

4. Cognitive Distancing. When you are upset, tell yourself that it is your judgement that upsets you and not, e.g., external events or the actions of others. First of all, then, try not to be swept along by the impression but delay responding to the situation until you have had time to regain your composure and self-control (Enchiridion, 20). Likewise, when you have the automatic thought that something is pleasurable or desirable, be cautious that you don’t get carried away by appearances, but generally delay your response (Enchiridion, 34). Then contemplate together both the experience of enjoying the pleasure and any negative consequences or feelings of regret that are likely to follow; compare this to the image of yourself praising yourself for abstaining from it (Enchiridion, 34). When some apparent misfortune befalls you, consider how you would view it if it befell someone else, e.g., when someone else loses a loved one we might say, “Such things happen in life” (Enchiridion, 26).

5. Empathic Understanding. When someone acts like your enemy, insults or opposes you, remember that he was only doing what seemed to him the right thing, he didn’t know any better, and say: “It seemed so to him” (Enchiridion, 42). When you witness someone apparently doing something badly, abandon your value judgement and stick with a description of the bare facts of his behaviour, because you cannot know what he did was bad without knowing his judgements and intentions (Enchiridion, 45).

6. Physical Self-Control Training. Train yourself, in private without making a show of it, to endure physical hardship and renounce unnecessary desires, e.g., practice drinking only water, or when thirsty holding water in your mouth for a moment and then spitting it out without drinking it (Enchiridion, 47). Withdraw your aversion (or desire to avoid) from things not under your control and focus it instead on what is against your own nature (or unhealthy) among your own voluntary judgements and actions (Enchiridion, 2). Likewise, abandon desire for things outside of your control. However, Epictetus also advises students of Stoicism to temporarily suspend desire for the good things under their control, until they have a firmer grasp of these things (Enchiridion, 2). Engage in physical exercise, but primarily to develop your psychological endurance and self-discipline rather than your body.

7. Impermanence & Acceptance. Contemplate the transience of material things, how things are made and then destroyed over time, and the temporary nature of pleasure, pain, and reputation. View external things as gifts on loan from the gods and rather than say “I have lost it” say “I have given it back” (Enchiridion, 11). Think of the essence of things, and what they really are.

8. Act with the “Reserve Clause”. At first, rather than being guided by your feelings for or against things (desire or aversion), use judgement to guide your voluntary actions (or “impulses”) toward and away from things, but do so lightly and without straining and with the “reserve clause”, i.e., adding “Fate permitting” to every intention to act upon externals (Enchiridion, 2).

9. Natural Affection (Philostorgia) & Philanthropy. Contemplate the virtues of both your friends and enemies. Empathise with everyone. Try to understand their motives and imagine what they are thinking. Praise even a spark of strength and wisdom and try to imitate what is good. Ask yourself what errors might cause those who offend you to act in an inconsiderate, unhappy or unenlightened manner. Love mankind, and wish your enemies to become so happy and enlightened that they cease to be your enemies, Fate permitting.

10. Affinity (Oikeiôsis) and Cosmic Consciousness. Think of yourself as part of the whole cosmos, indeed imagine the whole of space and time as one and your place within it. Imagine that everything is inter-connected and determined by the whole, and that you and other people are like individual cells within the body of the universe.

Evenings

1. The Retrospective Evening Meditation

Mentally review the whole of the preceding day three times from beginning to end, and even the days before if necessary.

1.1. What done amiss? Ask yourself what mistakes you made and condemn (not yourself but) what actions you did badly; do so in a moderate and rational manner.

1.2. What done? Ask yourself what virtue, i.e., what strength or wisdom you showed, and sincerely praise yourself for what you did well.

1.3. What left undone? Ask yourself what could be done better, i.e., what you should do instead next time if a similar situation occurs.

2. Relaxation & Sleep

2.1. Adopt an attitude of contentment and satisfaction with the day behind you. (As if you could die pleased with your life so far.) Relax your body and calm your mind so that your sleep is as tranquil and composed as possible, the preceding exercise will help you achieve a sense of satisfaction and also tire your mind.

CONTINUE TO REPEAT THIS PROCESS EVERY DAY

Appendix: Summary of Stoic Practices

To give you an idea of the breadth of Stoic practice, I’ve added a bullet-point list of some of the techniques found in the literature…

- Contemplation of the Sage: Imagine the ideal Sage or exemplary historical figures (Socrates, Diogenes, Cato) and ask yourself: “What would he do?”, or imagine being observed by them and how they would comment on your actions.

- Contemplating the Virtues of Other People: Look for examples of virtues among your friends, family, colleagues, etc.

- Self-Control Training: Take physical exercise to strengthen self-discipline, practice drinking just water, eat plain food, live modestly, etc.

- Contemplating the Whole Cosmos: Imagine the whole universe as if it were one thing and yourself as part of the whole.

- The View from Above: Picture events unfolding below as if observed from Mount Olympus or a high watchtower.

- Objective Representation: Describe events to yourself in objective language, without rhetoric or value judgements.

- Contemplation of Death: Contemplate your own death regularly, the deaths of loved ones and even the demise of the universe itself.

- Premeditation of Adversity: Mentally rehearse potential losses or misfortunes and view them as “indifferent” (decatastrophising), also view them as natural and inevitable to remove any sense of shock or surprise.

- The Financial Metaphor: View your actions as financial transactions and consider whether your behaviour is profitable, e.g., if you sacrifice externals but gain virtue that’s profitable but, by contrast, “What does it profit a man if he gains the whole world but loses himself.”

- Accepting Fate (Amor Fati): Rather than seeking for things to be as you will, rather will for things to be as they are, and your life will go smoothly and serenely.

- Say to External Things: “It is nothing to me.”

- Say Over Loved-Ones: “Tomorrow you will die.”

- Cognitive Distancing: Tell yourself it is your judgement that upset you and not the thing itself.

- Postponement: Delay responding to things that evoke passion until you have regained your composure.

- Picture the Consequences: Imagine what will happen if you act on a desire and compare this to what will happen if you resist it.

- Double Standard: When something upsetting happens to you, imagine how you would view the same thing if it befell someone else and say, “Such things happen in life.”

- Empathy: Remember that no man does evil knowingly and when someone does what doesn’t seem right, say to yourself: “It seemed so to him.”

- Contemplate the Transience of all Things: When you lose something or someone say “I have given it back” instead of “I have lost it”, and view change as natural and inevitable.

This is a brief excerpt from my book, The Philosophy of Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy, published by Routledge and available to order online from Amazon, and everywhere they sell books.

The Nature of the Good in Stoicism

Copyright © Donald Robertson, 2012. All rights reserved.

In a sense, the most fundamental question posed by ancient Stoicism was: “What is the nature of the good?” Wisdom, the essential virtue, was sometimes said to consist in having a firm grasp of the difference between the good, the bad, and the indifferent, and the ability to apply this knowledge to specific situations. However, the Stoics defined the good in a number of different ways. It’s clear that virtue or “excellence”, in accord with nature, is the chief good in life, particularly the cardinal virtue of wisdom. However, the Stoics also repeatedly equate the good with the “beneficial” (or “helpful”), the “profitable”, the “honourable” (or “beautiful”), and other terms.

Indeed, both Stobaeus and Diogenes Laertius report that for the original Stoics the good was understood primarily as “benefit” (ôpheleia), for example, in the sense that a physician might “benefit” or “help” his patient, or an army might help or support an ally. This may particularly be of interest to those, like myself, who wish to relate Stoicism to modern psychological therapy. What the Stoics meant by someone “benefitting” themselves, in accord with their essential nature as a rational animal, may arguably be interpreted as meaning something not to what we mean by helping (or “healing”) someone psychologically, through therapeutic processes.

Hence, the good is most generally “that which is such as to benefit”, and that the bad is understood as “that which is such as to harm”. Elsewhere, Diogenes Laertius says very clearly “For just as heating, not cooling, is a property of the hot, so benefitting, not harming, is a property of the good” (to agathou to ôphelein, ou to blaptein). And he explains: “To benefit [ôphelein] is to set in motion or sustain in accordance with virtue; whereas to harm is to set in motion or sustain in accordance with vice.” Hence, according to Diogenes Laertius, the virtues are good, and the additional qualities of every good (agathon) are given as:

- Beneficial or helpful (ôphelimon), “because it is such as to benefit”

- Advantageous or expedient (sumpheron), “because it brings such things as we are benefitted by when they occur”

- Morally binding, a duty (deon), “because it holds together in cases where this is needed”

- Profitable, repaying more than was expended (lusiteles), “because it pays back what is expended on it, so that it exceeds in benefit a mere repayment of the effort”

- Useful for things (chreisimon), “because it makes available the use of a benefit”

- Well-used or artfully-used (euchrêston), “because it renders the use of it praiseworthy” (by contrast, the indifferents are typically said to be capable of being used either well or badly)

- Honourable or beautiful (kalon), “because it is symmetrical with its own use” also “because it has all the features sought by nature or because it is perfectly symmetrical” and “the honourable uniquely means that which makes those who possess it praiseworthy; or a good which is worthy of praise; otherwise: what is naturally well suited for its own function; otherwise: that which adorns [its possessor], [as] when we say that only the wise man is good and honourable.”

- Worth choosing or to be chosen (haireton), “because it is such that it is reasonable to choose it”

- Just or fair (dikaion), “because it is consonant with law and instrumental to a sense of community”

Stobaeus gives a similar list, saying that “all good things are”:

- Beneficial as opposed to harmful

- Well-used as opposed to ill-used

- Advantageous as opposed to disadvantageous

- Profitable as opposed to unprofitable

- Virtuous as opposed to base

- Fitting as opposed to unfitting

- Honourable as opposed to shameful

- “…and there is an affinity to them” and with bad things “there is no affinity to them”

However, he goes on to say, once more, that “benefit” is the fundamental sense of the good in Stoicism.

The definition of the good is, moreover, divided into three senses by the Stoics, as follows, according to both Diogenes and Stobaeus:

- Virtue: “The good is that from whichbeing benefited is a characteristic result”

- Virtuous actions: “It is that according to which[being benefited] is a characteristic result, for example, action according to virtue”

- Virtuous men: “It is he by whom [being benefited is a characteristic result]; and ’by whom’ means, for example, the virtuous man who participates in virtue.”

According to Diogenes Laertius, goods are also defined as internal, external, or neither:

- In the soul: Virtues and virtuous actions

- External: Having a virtuous fatherland and friend, and their happiness

- Neither: Someone in and for himself to be virtuous and happy

Goods are also final, instrumental, or both:

- Instrumental: “a friend and the benefits derived from him”

- Final: “confidence and prudence and freedom and enjoyment and good spirits and freedom from pain and every virtuous action are final”, but he implies below that the primary final good is “happiness”

- Both: “The virtues are both instrumental and final goods. For in that they produce happiness they are instrumental goods, and in that they fulfil it, such that they are part of it, they are final goods.”