[This is just a first draft so don’t worry too much if there are some typos or bits you don’t agree with — I’ll probably just change it later!]

When people first begin studying Stoicism it’s inevitably not long before they encounter debate involving various criticisms of the philosophy. All of these criticisms are, in a sense, legitimate. Of course, it’s natural and healthy for us to engage in these sort of philosophical discussions, especially if we can shed some light on things for ourselves or others. However, the majority of these criticisms – at least the ones I’ve heard over the past ten or fifteen years – tend to be based upon simple misconceptions about Stoicism, which can be answered fairly easily if we take the time to do so. I’ve therefore chosen to try to summarise the main arguments in one article and to provide an overview of them and the way I’d normally tend to reply. I don’t really have space here to go into all of these matters in a great deal of depth – so some people are bound to find my replies insufficient as they stand – but I think the brief comments below may provide a good indication of some ways to answer the criticisms I’m talking about and I’m sure others can develop them further.

In the Beginning was the Word

The most common source of misconceptions about Stoicism is simply the word itself. “Stoicism” is a homonym: it sounds identical, and is spelt the same, as another word, which nevertheless means something fundamentally quite different. There are two different things called by this name, in other words. The difference is usually indicated by capitalisation.

- The word “Stoicism” with a capital “S” refers to an ancient Greek school of philosophy, defined by its central ethical tenet: that “virtue” (or excellence of character) is the only true good.

- The word “stoicism” with a small “s” is a modern expression, referring to a personality trait, which involves calmness in the face of adversity but is also often taken to imply a lack of emotion in general.

Indeed, it’s not a coincidence that both things are called by the same name. The personality trait is named “stoicism” because of the ancient school of philosophy. However, the relationship between these concepts is tenuous and quite problematic.

The ancient philosophical school of Stoicism does not, in fact, advocate being “stoic”, in the sense of being unemotional, as we shall see. It’s also misleading because people talk about having a naturally “stoic” temperament whereas “Stoicism” consists of a philosophical world-view and set of values. Someone may have a “stoic” personality but hold completely different beliefs from someone who is “Stoic” in the philosophical sense of the word. In particular, people today often describe someone as “stoic” who believes that something genuinely bad has happened to them, perhaps bankruptcy or divorce, but keeps a “stiff upper-lip” despite their upset. That person would not be a “Stoic” in the philosophical sense, though, because, as we’ll see, although he may rationally “prefer” not to be bankrupt or divorced, a Stoic philosopher would not judge these things to be intrinsically bad to begin with.

Philosophy, what Philosophy?

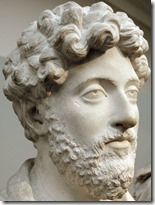

By far the most popular and widely-read book on Stoicism is The Meditations of the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius. It’s a wonderful book and represents Marcus’ attempts to train himself in Stoic practices, while recording his maxims and reflections in the form of a contemplative journal. However, it’s therefore not a systematic treatise on Stoic philosophy. Because Marcus was writing for himself, in a kind of aphoristic style, he did not generally take time to make his philosophical assumptions explicit. Nevertheless, Stoicism was famous in the ancient world for its highly systematic nature. Scholars who are familiar with the doctrines and arguments of Stoic philosophy, and its technical terminology, easily spot that Marcus is working within that system. However, for most readers this is simply not apparent and so I’ve heard intelligent people say that Marcus was just writing down his “random musings” and nothing more. For that reason, many individuals, having read only The Meditations and not any other Stoic texts or modern commentaries, naturally tend to assume that Stoicism is a loosely-defined set of ideas. The opposite is the case, though.

Stoicism is a tightly-integrated, formal, philosophical system. It was founded in 301 BC in Athens by Zeno of Citium and Marcus, who happens to be pretty much the last famous Stoic we find in history, died in 180 AD. So the Stoic school of philosophy survived for almost 500 years, half a millennium, as a living, practical and theoretical tradition. Thousands of books were apparently written on Stoicism in the ancient world, although less than 1% of that literature survives today. Zeno himself was known for the “laconic” brevity of both his sayings and arguments. However, Chrysippus, the third head (“scholarch”) of the Stoic school, engaged in much more elaborate philosophical arguments than Zeno and supposedly wrote over 700 books (although perhaps short books, more like essays). I suspect that he probably felt that it was necessary to elaborate upon the doctrines of the school in this way in order to defend them against equally elaborate criticisms of Stoicism, which were taught and published by philosophers aligned with other schools of philosophy, particularly the Skeptics of the Platonic Academy. In any case, Stoicism was always renowned as a highly sophisticated and coherent system of philosophy, with a complex technical vocabulary and an extensive armamentarium of practical psychological strategies at its disposal. Criticisms often fail to take account of that by interpreting passages in isolation, without reference to the rest of the philosophical framework on which individual ideas or practices depend.

Why Just Pick on the Stoics?

Another common pattern that emerges when we look at criticisms of Stoicism is that they’re often, on closer inspection, highly skeptical arguments, of a very broad nature. They would would apply much more generally than their author is letting on. For example, a speaker at our 2015 conference on Stoicism forwarded the criticism that Stoic practices should not be taught in schools because they could be exploited to make children take on excessive responsibility for their emotional distress, and thereby disguise the role of the environment and socio-political factors. However, it seems to me that this argument does not specifically apply to Stoicism but to more or less any form of resilience-building or psychological self-improvement whatsoever. It’s much less tempting accept such an argument when we realise its scope extends so widely.

Likewise, as we’ll see below, Stoicism is also often criticised because its ethical doctrines can’t be conclusively proven with either philosophical or empirical arguments. However, that’s also true of ethics in general, including ethical doctrines based on Christian, Buddhist, Marxist, humanist, and all other religions and philosophies. Of course, just noticing this problem with the criticism isn’t sufficient to answer the criticism. However, for many people, it does weaken its appeal somewhat. It’s also often the case that criticisms of Stoicism are so general in scope that they would undermine beliefs that the speaker is already committed to holding themselves, leaving them in a position of self-contradiction, although this may not be apparent at first glance.

Many of the criticisms of Stoicism that I’ve heard try to argue that it can’t be healthy or effective psychologically, on the basis of some objection to the cognitive theory of emotions. However, cognitive-behavioural therapy is based on a very similar model of emotion and employs similar strategies. CBT has proven its effectiveness in many hundreds of highly-sophisticated clinical trials. The fact that it’s safe and beneficial, overall for a range of conditions, is pretty much beyond reasonable doubt now. Yet sometimes criticisms of Stoicism ignore this overlap and, in certain cases, if we took them seriously they should lead us to discount something that we know works, from empirical evidence, which would be an absurd conclusion. Questions about the effectiveness of Stoic strategies as a therapy for the emotions can only be settled by consulting relevant scientific evidence because it’s an empirical question, not a purely philosophical one. Armchair discussions about the effectiveness of therapies should set our alarm bells ringing. This kind of idle speculation is surprisingly common, though. It’s more obvious that these arguments are vacuous if we consider how they would fare in relation to cognitive-behavioural therapy rather than just Stoic therapy.

The Unproven Ethics of Stoicism

As mentioned above, one of the most common criticisms of Stoicism is that its ethical doctrines cannot be philosophically proven. Although the ancient Stoics believed that they could provide rigorous proofs of their main conclusions, and defend them against radical ethical skepticism, we’re told they were mistaken. Now, funnily enough, there’s undoubtedly some validity to this criticism. However, it has to be understood in the following context: no philosophical or non-philosophical system of ethics has ever provided a conclusive proof of its doctrines. So this extremely-skeptical criticism would apply not just to Stoicism but to ethics in general, and often to ethical assumptions held by the person making the criticism. Even if the ethics of Stoicism can’t be proven conclusively, many people obviously feel that it can be shown to be consistent with their own deepest ethical convictions, on reflection, and to lead to a coherent ethical world-view. That’s often enough for them and is arguably all that we can ask for in terms of a philosophical justification for ethics.

It’s sometimes also claimed that Stoic Ethics depends on the assumption that a provident God exists and that without this premise, which many modern readers reject, its ethical system loses its foundation. However, as we’ll see below, the Stoics were pantheists who believed in a “philosophers’’ god”, radically different from the Zeus of Greek mythology or the Judeo-Christian Jehovah. The Stoics were also materialists of a sort and their God is synonymous with Nature as a whole. Many people who reject the idea of the Christian God or the supernatural beings described in Greek mythology (assuming we take it literally) would be more willing to accept the notion that Nature as a whole can be viewed as an active process, from which certain values might somehow be derived. The main issue at stake is whether Nature can be viewed in teleological terms, as having some kind of ideal or goal, in reference to which other values could be established. Although that’s a view that many people reject in theory, it’s worth noting that most people in their daily lives act as if they were committed to the assumption that things naturally have an optimum or ideal state. For example, we would find it very difficult to suspend any thinking that employs the concept of something (ourselves and other people included) being “helped” or “harmed” by events. However, that way of talking, thinking, and acting arguably betrays the fact that we’re already committed to a world-view in which there’s a desirable state that things “should” be allowed to be in. Of course, the Stoics would argue that we’re all wrong to think that physical injury, financial loss, and attacks on our reputation are genuinely “harmful” but I believe that’s an easier step to take than trying to argue against the extreme form of skepticism that denies the possibility of any meaningful goal in nature whatsoever. To put it another way: although this type of ethical skepticism might seem difficult to counter, I don’t think many people are really able to view the world that way in practice anyway. For the Stoics, Nature’s goal for man is “virtue”, for him to excel and flourish in his use of practical reason. So very simply: virtue helps him and vice harms him: everything else is “indifferent” in this regard.

Moreover, the Stoics actually seldom appeal to theological premises, about the existence or nature of God, in order to justify their ethical conclusions anyway. They forward many other lines of argument to support their central claim that the supreme goal of life is virtue, or excellence of character. (Not just because Zeus wills it.) For instance, to take just one example, they argue that to judge something “good” is to desire it, and that it makes no sense to desire something that is not under our control, therefore the good must reside in some quality of our own voluntary actions, and good actions are what we mean by virtue. (To be fair this proto-Kantian argument – “should entails can” – isn’t very explicit but I believe the Stoics allude to it and it’s easy to see how it would be consistent with their surviving remarks.) They also argue that on reflection we tend to praise and admire other people not for their possessions but for the character of their voluntary actions, for “virtues” or good qualities such as wisdom, justice, courage, and self-discipline, and it would be inconsistent or hypocritical of us not to value and desire the same thing (virtue) for ourselves. Whatever we make of these and other Stoic Ethical arguments, it’s simply not true that, in any obvious sense, they require us to agree with archaic metaphysical or theological assumptions. I believe we could make the same sort of arguments today, from the perspective of modern scientific atheism or agnosticism, and defend them with additional arguments drawn from that world-view, without contradicting Stoicism’s central doctrines.

Stoics Have Feelings Too

Many people mistakenly assume that Stoics seek to “repress”, “suppress”, or “eliminate” all of their emotions. Sometimes this is described as the assumption that Stoics are like the character Mr. Spock from Star Trek, or that they are unemotional like a “cold fish”. To be fair, even some highly-regarded academic scholars have, in the past, argued that Stoicism teaches the “extirpation” (uprooting and elimination) of all emotions. However, I think few experts on Stoicism today would accept that interpretation. First of all, it’s difficult to imagine why Stoicism would have been so successful in appealing to so many different people, for so many hundreds of years, if what it taught us was that we should eliminate all of our feelings, even the pleasant and seemingly healthy ones. Also, much of our emotional life is not entirely “up to us”, and battling “stoically” against our automatic emotional reactions is bound to seem totally contrary to the well-known Stoic teaching that we should focus on changing things we control while accepting that some things are not within our power.

Moreover, it should probably be explained that the Stoics don’t even use a word that could be translated, unequivocally, by the English word “emotion”. They talk mainly about “passions” (pathê), a technical term that has a very specific meaning in their philosophical system. Passions were defined as both desires and emotions, which are “irrational”, “excessive”, and “unnatural” (in the sense of being unhealthy). These “passions” are also intended to be voluntary: we implicitly choose to indulge in them and perpetuate them. So the Stoics primarily advise us to stop going along with them. It’s also important to explain that for Stoics there is no real division between reason and the passions, or emotions. It was Plato’s doctrine that reason and the emotions are two fundamentally separate parts or faculties of the mind, and the Stoics criticised and totally rejected that assumption. The emotion of fear, for example, consists of certain anxious feelings, but it also necessarily entails the judgement that something bad or harmful is about to happen, otherwise it just wouldn’t be fear.

When people talk about “repressing” or “suppressing” emotions – two terms which, incidentally, mean very different things – they usually have a vague idea in mind, of forcefully eliminating the feelings or sensations, without changing the beliefs associated with them. So someone who suppresses fear would perhaps be trying to relax their muscles, slow their breathing, act outwardly courageous, and block the feelings of anxiety from their mind, while still believing that something bad is about to happen. Someone who does not believe that something bad is about to happen, probably won’t have any need to suppress their feelings in this way, though. It doesn’t really make sense to talk about repressing or suppressing anxious feelings when the fearful belief has gone, and (under normal circumstances) anxiety abates naturally as a result. That’s what the Stoics meant, though: changing the belief rather than merely suppressing the feelings. They also don’t mean simply forcing the belief to change but rather they argued that the beliefs underlying unhealthy passions are false, and that we should change them by thinking things through philosophically until we actually realise that they are mistaken. For instance, the Stoics don’t tell us to try to suppress our anxiety about death. Rather they argue, on the basis of their philosophy, that death is not intrinsically bad, or evil. (For example, some people may choose euthanasia, in extreme circumstances such as severe illness, which suggests that death is not perceived by them as worse than the prospect of an unpleasant future life.)

Moreover, the Stoics explicitly stated that their philosophy contained a systematic model, which distinguishes between three categories of passion (or desires and emotions):

- “Passions” (pathê), which are irrational, excessive, unhealthy, and voluntarily perpetuated by us

- “Proto-passions” (propatheiai), which are the involuntary or reflex-like precursors of full-blown passions (desires and emotions), and the Stoics name examples such as shaking, sweating, being startled, stammering, blushing, etc.

- “Good passions” (eupatheiai), which are rational, moderate, healthy, and voluntary passions, which “supervene” upon wisdom and virtue, because they are the consequences of holding true beliefs about what is good, bad, and indifferent in our lives

The “good passions”, experienced by the Stoic Sage, or the “wise and good” person, are things like joy (happiness) about our own good qualities (virtues) or those of others, desire for ourselves and others to flourish and become better people, fate permitting, and a healthy concern about the possibility of falling into foolishness or vicious attitudes and behaviour. That’s right, the Stoic ideal consists of feeling abundant joy! It also consists of a kindly and benevolent attitude, which the Stoics describe as being like a gentle friendship felt toward our own selves, and the rest of mankind. Indeed, Stoic Ethics is based on the idea that humans naturally tend to experience an instinct called “natural affection” (philostorgia) for our own offspring, and family. The wise man gradually extends this into brotherly-love for all mankind, a kind of philanthropic attitude, linked to what we call Stoic “cosmopolitanism”, seeing all human beings as fundamentally brothers and sisters, and part of the same global community. Marcus Aurelius described this very succinctly, in a way that obviously contradicts the “cold fish” misconception about Stoicism, when he said that the Stoic ideal is to be “free from the [irrational, unhealthy] passions, and yet full of love.”

Zeus, the Philosophers’ “God”

The ancient Stoics, particularly Epictetus, frequently refer to the Greek god Zeus in very religiously-devout-sounding language. (Sometimes they refer to him under other names, such as “God” or “Jupiter”, or to other Greek or Roman deities.) This leads many modern readers to assume that the ancient Stoics require us to “believe in God” in order to share in their philosophy, and if they happen to be atheists or agnostics, as many people are today, that can be somewhat off-putting. However, the Stoics were renowned for basing their philosophy on concepts that radically revised the values and assumptions prevalent in their society. They followed their predecessors the Cynics, and other philosophers, in doing this, and it is known as philosophical paradox, which literally means not just something puzzling but specifically something “contrary to (popular) opinion”. The prevalent opinion about the gods, the opinion held by of the majority of ancient Greeks, was that they were literally the sort of characters described in the myths: supernatural beings, with human-like personalities and emotions, etc. However, the Stoics held a completely different view, which so challenged popular theology that throughout history they – and philosophers like them, such as Spinoza – were frequently accused of being atheists by Christians and other theists.

The Stoics were pantheists of sorts (or “panentheists”) who believed that the whole of Nature is divine, and so they referred to the whole of Nature as “Zeus”. They were also materialists of sorts (or “corporealists”) who utterly rejected the notion of any metaphysical realm beyond the physical universe, such as Plato’s theory of forms. They are believed to have largely assimilated the philosophy of Nature taught by the famously paradoxical and cryptic pre-Socratic philosopher Heraclitus. In typically equivocal style, Heraclitus taught that Nature is “both willing and unwilling to be called by the name of Zeus”. I would say that if we asked Heraclitus whether “Nature” was the same thing as “Zeus” or “God”, he would reply: “yes and no”. Moreover, I think that his successors the Stoics, if pressed on this question, would also give the same reply. The Stoics were renowned in the ancient world for their attempts to reinterpret Greek myths allegorically, usually as metaphors for natural elements and processes. For example, for the Stoics, Zeus is not literally a supernatural being, resembling a bearded man who hurls bolts of lightning from atop Mount Olympus. Rather the myth of “Zeus” is a metaphor for the natural “fire”, the force or energy, that animates the whole of the physical universe, or it is Nature viewed as an active process.

In his Republic, probably the founding text or original manifesto of Stoicism, Zeno reputedly described “as if in a dream”, a utopian vision of the ideal philosophical society. In it there would be no shrines or temples. The Pharsalia, a much later epic poem written by Seneca’s nephew, the Stoic Lucan, contains a scene in which the great Stoic hero of the Roman Republic, Cato of Utica, is advised by one of his officers to consult the priests in a temple to Zeus, and seek their prophesy about the outcome of an impending battle with the legions of the tyrant Julius Caesar. However, Cato says no. He basically says that Stoics don’t really believe in temples, or prophecies, of this kind. Zeus is Nature, therefore he is present everywhere, and there are not really any special buildings in which he lives, and no special individuals (priests or prophets) through whom he speaks. Nature runs through everything including the human mind, and so Cato looks deep within his own soul to commune with the divine by contacting his own deepest convictions and instincts and there he finds the doctrine of Stoicism that says whatever fate befalls us, all that truly matters is that we handle it virtuously, with wisdom and integrity. He doesn’t need a priest to tell him that. So we’re told he turned his back on the temple and walked away without even bothering to go inside. The Stoic “Zeus” is Nature, and Nature has no use for temples or churches, scriptures and rituals, or priests and prophets. Epictetus tells us that although Stoics might pray, they did not pray as the majority did. They didn’t petition the gods for favours. They didn’t pray for Zeus to bring rain for crops, or victory in battle, but rather they prayed for only one thing: to find wisdom within themselves and thereby to flourish as human beings.

This concept of a “sort-of” God – both willing and unwilling to be dubbed “Zeus” – is sometimes called the “philosophers’ God” and it’s so radically different from what most people mean by “God” that many agnostics or atheists may actually find it entirely acceptable – or at least, more acceptable – to their world-view. Indeed, pantheism in general has often been viewed as a spiritual view which comes across as much more palatable than religions such as Christianity or Islam do to modern, scientifically and skeptically-inclined, individuals. The physicist Albert Einstein, for example, said that he could not believe in the God of Christianity or Judaism but that he preferred to believe in the God that Spinoza described as “Deus sive Natura”, which basically means “God” as a synonym for the unfolding process of Nature as a whole. This pantheistic God advocated by Einstein and Spinoza is therefore very similar to the Zeus of the Stoics.

Stoics Prefer Things; Cynics Don’t

Another common group of criticisms about Stoicism have to do with the claim that it treats all external things as totally indifferent, and that Stoics have no desire to change anything whatsoever in the world. This takes various forms but it’s often allied with the claim that Stoics passively accept bad personal, political, or social situations, which most people would think we have an obligation to try to change. The first thing to say in response to this is that as a matter of historical fact, the Stoic school was always particularly renowned for advocating political involvement among its followers. For example, Zeno had King Antigonus of Macedonia, the most powerful military and political leader in the region, as a student and presumably discussed ethical doctrines with him that would have implications for the way he ruled. Antigonus pleaded with Zeno to travel to his court and become his advisor but by that time he was an elderly man and somewhat too frail for the upheaval this would involve so he sent one of his finest students, Persaeus, instead, and we learn that he was put in charge of the city of Corinth and later died in battle commanding the garrison during its defence against Antigonus’ enemies.

Likewise, the great Stoic hero Cato of Utica was famous for his political stubbornness and unflinching opposition to the rise of the tyrant Julius Caesar. Seneca’ nephew, Lucan’s epic poem, Pharsalia, describes Cato’s involvement in the Roman Civil War in heroic terms, particularly the scene where he finally takes command of the shattered remnants of the Republican army and marches them through the deserts of North Africa to make their last stand against Caesar’s legions at the fortified city of Utica. Cato was not a doormat, in other words. He was held up throughout Roman society as an exemplar of the Stoic virtues of courage and self-discipline, in the face of extreme adversity. We might also point to (today) the most famous Stoic, Marcus Aurelius, who also led a broken Roman army, weakened by plague, in a desperate but successful attempt to drive back invading barbarians hordes. We’re told Marcus took emergency measures, which shocked the populace, such as conscripting gladiators into the army, and selling off many of his own treasures from the imperial palace to help fund the war effort. Stoicism clearly did not lead him to sit back and twiddle his thumbs in passive resignation while the Marcomanni hordes overran and looted Roman cities. If he’d lost that campaign and Rome had fallen, the world as we know it today would not exist. He took to the battlefield and we’re told the legions under his command especially loved and revered him – the soldiers reputedly wept when his death was announced. These were, therefore, all clearly men of action – exceptionally so.

So how is it possible for so many people to get the opposite idea: that Stoicism teaches us to be overly-passive or submissive? This misconception basically stems from a tendency to confuse it with its precursor, the philosophy of Cynicism. Zeno, the founder of Stoicism, was originally a student of the famous Cynic philosopher Crates of Thebes. For many years, therefore, Zeno was a Cynic but he founded the Stoic school, after training in philosophy for about twenty years, because he became dissatisfied with Cynicism and the other Socratic schools in Athens. The Cynics believed that virtue is the only true good, vice is the only true evil, and that everything else is totally indifferent with regard to the goal of life. Zeno and his Stoic students accepted this view but they also felt it was necessary to make a fundamental change to it. So Zeno introduced an innovative concept which became known as the central and most characteristic teaching of the Stoic school: the doctrine of “preferred indifferents”. This teaching says very simply that although the Cynics were right that only virtue can be considered “good” (and vice “bad”) in the strictest sense of the word, it is nevertheless necessary for the wise man to distinguish between external things that he “prefers” to get or to avoid.

The Stoics provide very clear lists of these things. For example, physical health, wealth, and good social standing, are “preferred”, and their opposites are “dispreferred” – it’s perfectly rational for the Stoic to prefer not to become ill, impoverished, or to be condemned or exiled. When the Stoics describe these things as “indifferent” they mean that they’re of no relevance when it comes to the good life. Socrates may have been starting to age, relatively poor, and condemned to death by unjust accusers and the Athenian court but he nevertheless lived a good life, an exceptionally better life in fact than the majority of other people, because he dealt with such adversity wisely and with courage. The Stoics would say that his poverty did not actually make his life any worse but rather, if anything, it actually gave him more opportunity to exercise his virtues and strength of character, and to flourish as a wise and good man. Despite this particular sense in which they lack value, though, some externals are considered to be naturally preferable over others and wisdom consists in choosing prudently between them, without compromising our virtues. Chrysippus reputedly summed this up by saying, to paraphrase him somewhat, that to the Stoic Sage it’s ultimately indifferent whether or not he’s able to have a bath, because it won’t make him any more or less enlightened, but that given the opportunity, he would certainly prefer to be able to wash when he’s dirty.

It’s perfectly natural and rational therefore for Stoics to continue to seek certain “preferred” things in life, and it would be foolish for them not to do so. This perhaps involves an element of speculation on my part but, personally, I suspect that in the Republic, when Zeno described the ideal Stoic society, what he said was that this is the ultimate external goal of the wise man, the highest preferred indifferent, which he would presumably have to pursue with the Stoic “reserve clause” in mind. In other words, the wise man only rates his wellbeing in terms of attaining wisdom and virtue but his practical actions aim toward improving the world and the lives of other people, by spreading wisdom and virtue among them. Zeno himself did this, for example, by lecturing in public, at the Stoa Poekile, where anyone could come and hear him speak, and by writing books intended to help others improve, even after his death. Antigonus, Cato, and Marcus, would not have wrestled with the world of politics, or risked their lives on the field of battle, and Zeno and the other Stoic scholarchs would not have dedicated their lives to teaching and writing books if they did not believe that it was worthwhile trying to change the world in a way that seemed definitely “preferable” to them, and it would be better for them even to try and fail in doing so than never to have tried at all.

The wise man will not be angry with sinners. Why not? Because he knows that no one is born wise, but becomes so: he knows that very few wise men are produced in any age, because he thoroughly understands the circumstances of human life. Now, no sane man is angry with nature: for what should we say if a man chose to be surprised that fruit did not hang on the thickets of a forest, or to wonder at bushes and thorns not being covered with some useful berry? No one is angry when nature excuses a defect. The wise man, therefore, being tranquil, and dealing candidly with mistakes, not an enemy to but an improver of sinners, will go abroad every day in the following frame of mind: “Many men will meet me who are drunkards, lustful, ungrateful, greedy, and excited by the frenzy of ambition.” He will view all these as benignly as a physician does his patients.— Seneca, On Anger, 2.10

The wise man will not be angry with sinners. Why not? Because he knows that no one is born wise, but becomes so: he knows that very few wise men are produced in any age, because he thoroughly understands the circumstances of human life. Now, no sane man is angry with nature: for what should we say if a man chose to be surprised that fruit did not hang on the thickets of a forest, or to wonder at bushes and thorns not being covered with some useful berry? No one is angry when nature excuses a defect. The wise man, therefore, being tranquil, and dealing candidly with mistakes, not an enemy to but an improver of sinners, will go abroad every day in the following frame of mind: “Many men will meet me who are drunkards, lustful, ungrateful, greedy, and excited by the frenzy of ambition.” He will view all these as benignly as a physician does his patients.— Seneca, On Anger, 2.10 Begin the morning by saying to thyself, I shall meet with the busy-body, the ungrateful, arrogant, deceitful, envious, unsocial. All these things happen to them by reason of their ignorance of what is good and evil. But I who have seen the nature of the good that it is beautiful, and of the bad that it is ugly, and the nature of him who does wrong, that it is akin to me, not only of the same blood or seed, but that it participates in the same intelligence and the same portion of the divinity, I can neither be injured by any of them, for no one can fix on me what is ugly, nor can I be angry with my kinsman, nor hate him, For we are made for co-operation, like feet, like hands, like eyelids, like the rows of the upper and lower teeth. To act against one another then is contrary to nature; and it is acting against one another to be vexed and to turn away.— Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, 2.1

Begin the morning by saying to thyself, I shall meet with the busy-body, the ungrateful, arrogant, deceitful, envious, unsocial. All these things happen to them by reason of their ignorance of what is good and evil. But I who have seen the nature of the good that it is beautiful, and of the bad that it is ugly, and the nature of him who does wrong, that it is akin to me, not only of the same blood or seed, but that it participates in the same intelligence and the same portion of the divinity, I can neither be injured by any of them, for no one can fix on me what is ugly, nor can I be angry with my kinsman, nor hate him, For we are made for co-operation, like feet, like hands, like eyelids, like the rows of the upper and lower teeth. To act against one another then is contrary to nature; and it is acting against one another to be vexed and to turn away.— Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, 2.1

In a nutshell…

In a nutshell…